The Third Edition of the International Conference Series on Wine Active Compounds, affectionately known as WAC 2014, was an overwhelming success in many regards, but most notably in the bridging of disciplines. Partly a result of the participation of the UNESCO Chair “Culture and Traditions of Wine”, based at the University of Burgundy, the organizers of WAC strove toward the integration of natural and social sciences, rather unique for an international congress – particularly one that is, at its core, focused on wine chemistry. Social science lectures were interspersed throughout the conference, falling between the more traditional lab-based research talks, but always maintaining a coherent link to the session theme. In honor of the success of this project, I will be devoting a series of posts to exploring some of the themes that were brought to light during the convention, including the regulation of enological practices, role of the sensory sciences, the notion of complexity, the neuroscience of perception, biodynamics, and the role of wine compounds in some key human diseases including Parkinson’s disease, Alzheimer’s, diabetes, metabolic disorders, intestinal inflammation and cardiac disease.

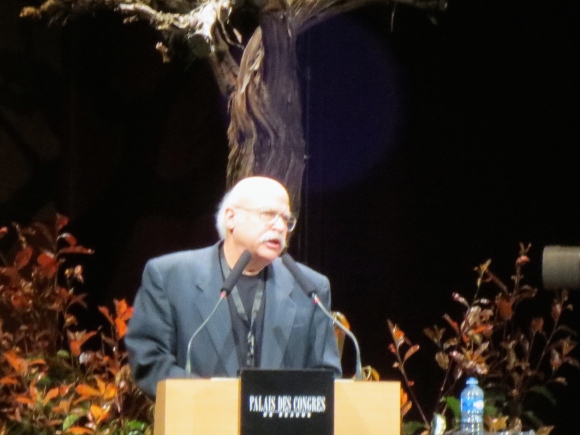

To kick off the series, I’ll begin with what for me was the most exciting talk of the conference – the keynote given by Harvard historian of science Steven Shapin. I walked into the first day of WAC 2014 with stars in my eyes, as after 4 college years filled with as many History of Science and Science Studies courses as I could fit, to me Shapin is a true celebrity, and I’d had no idea that he took an interest in wine.

His talk was entitled “How does wine taste? Sense, science, and the market.” He dove right into a lecture about the history of how we describe what we taste in a wine. There is, he argues, a dramatic split that occurred in the 20th century, fundamentally altering the manner in which we talk about wine. And this division corresponds to significant scientific and market changes in the same period.

From the time of Aristotle up until the pre-WWII era, the specific lexicon used to describe wines was quite restrained, with only such words as “sweet”, “acute”, “austere” and “mild”, as well as terms for faulty wines, being regularly employed. Wines were more often described in terms of their medical properties or physiological effects, and people were more inclined to compare wine to poetry or particular emotions than to specific flavors. It wasn’t that people didn’t appreciate and evaluate wines – they certainly did as evidenced by the 1855 Bordeaux Classification – clearly wine aficionados were interested in differentiating and evaluating wines here, but they didn’t need to be able to describe the wines to make an opinion about it.

So what changed? How did we end up with the current trend, wines “described as more or less complex aggregates of individual [flavor] components” – an “analytical” approach that reduces a wine to a series of comparisons to other foods or smells? The answer, according to Shapin, lies in the interplay between scientific and market changes that occurred around the mid-20th century.

A general trend began in chemistry, biology and physics, resulting at least partially from increasingly powerful analytical techniques, toward a focus on constituents of substances or organisms rather than their more general qualities. The modern reductionist paradigm began to characterize science, attempting to understand systems by first understanding their constituent parts. This trend was reflected in the development of enology and sensory analysis in French and American institutions (notably the University of Bordeaux and UC Davis), where a focus on discovering the particular molecules in wine became paramount. The understanding of the molecular composition of wine aroma fit effortlessly with a sensory model that breaks the aroma into its individual components, each of which associated with a corresponding molecule that can be isolated and measured.

Ultimately, this type of reductionist description trickled down into consumer culture, but how? The key, says Shapin, was the concomitant expansion of New World wine drinking markets. Wine has always been associated with a certain prestige and connoisseurship, and these new consumers were seeking an accessible vocabulary with which they could discuss their newfound beverage of choice. The most accessible, setting aside the flowery, poetic descriptions of the past in favor of more direct and analytic language with a clear link to chemistry, was UC Davis sensory scientist Maynard Amerine’s lexicon of descriptors that were systematically associated with “real wine compounds” (published in 1976 and available on Amazon). This type of description was, perhaps most influentially, adopted by Robert Parker in his publication the Wine Advocate, the first edition of which was released in the same year as Amerine’s book.

Thus, argues Shapin, the style of tasting notes that remains most widespread even today, a list of individual flavors of which a wine is comprised, is not a natural consequence of physiological sensation. No, like all human activities, wine description has a historical background, a past linked to concrete events that have shaped how we understand and articulate our thoughts. Wine is, he says, “modernity in a glass”, bringing together the sensations of taste with the worldview of modern science and consumer culture.